An Interest In:

Web News this Week

- April 26, 2024

- April 25, 2024

- April 24, 2024

- April 23, 2024

- April 22, 2024

- April 21, 2024

- April 20, 2024

Demystifying state management

State management is one of the most complicated, and opinionated topics in modern and JavaScript-focused front-end development. But before diving in, what is state? State, in all its different forms, is nothing more than values we use to determine what to show towards our users and what behavior we allow. That is it. A global or application state is nothing more than a (complex) JavaScript object accessible from our UI code. We can read from it and we can change it. When we change it, we see the change or effect from the change reflected on the screen.

Types of states

Let's discuss the different types first. Many say they manage their state on a global level, using packages like Redux. But, people often forget that they use different types of states as well, even when they don't know it.

- Local: state that is used by a single UI component.

- Shared: state that is used by many UI components. It is often managed in a parent or wrapper component.

- Global: a special kind of shared state, as it lives on the highest level, accessible to all UI components (or even helper functions).

- Meta: also known as 'state about state'. It tells you something about

- Route: state stored in the current URL of the application (e.g. object IDs or pagination information).

- Remote: a copy of the data coming from a server. The responses of fetch requests are stored as 1-on-1 copies in this state. It should not deviate from the server (except when applying optimistic UI).

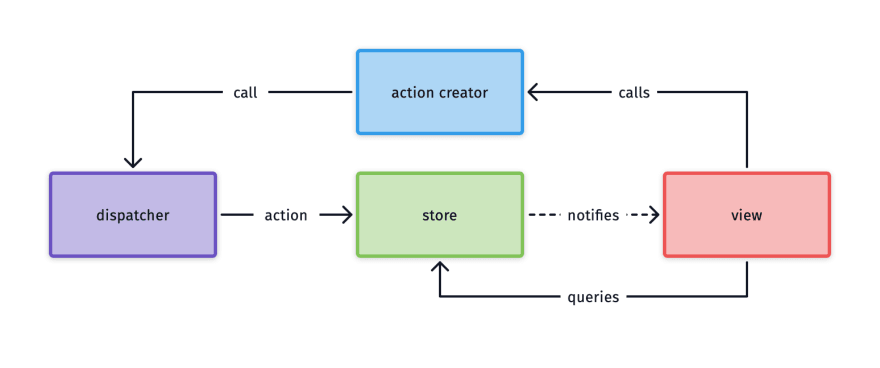

The above image is coming from a reference architecture from client-side applications. It is only used to visualize the different types.

You don't have to manage these types of states all by yourself, most of the time. Many packages can be used to help you around. When looking at the React eco-system, packages like Redux (global), SWR (remote), React Router (route, ), and React-Query (remote), are all good examples of packages that do a lot for you.

Event-driven

The best-known state management pattern is the flux pattern. It gained popularity with the 'Redux' package. It is a great example of an event-driven pattern. Let's take a closer look at its flow. The user, via the view, dispatches an action, via an action creator. The dispatched action is nothing more than a simple JavaScript object describing the type, and the payload. It is an event. Within the store, many different reducers act upon the dispatched event and change the content of the store. The view queries the store to display the correct information to the user. When changes happen, the store notifies the view.

A core concept within this pattern is the reducer pattern. A reducer is a function that takes a state object and action as input and returns a state object. Based on the action, it determines how to change the state for the output. This is often achieved by using a switch statement. But it can also be achieved using a strategy pattern. A big benefit of the strategy pattern is that each 'case' is a separate function. Makes variable naming inside a complex reducer a lot easier.

function action1(state, payload) { ... }function action2(state, payload) { ... }const strategies = { EVENT_1: action1, EVENT_2: action2, __default__: (s) => s}function reducer(state, { type, payload }) { const reduce = strategies[type] || strategies.__default__; return action(state, payload);}Event-driven state management is related to state machines. State machines allow us to model state more , in a way that can be visualized. Below is an example of a state machine for an animated toast message. This toast message should disappear after X seconds. Implementing something like this is easy when already using reducers. By adding if-statements, we can guard state changes: "You can do action X if we are in state Y".

Atomic

Most event-driven solutions go for a single global store. The atom pattern does it differently. Instead of having a single global state, we have many different global states of single values. The popularity of this pattern rose with the introduction of Recoil from Facebook. This pattern is often seen as easier. Because everything is a single value, you don't have the overarching boilerplate of action creators, actions, events, etc. You just have a global value, and when you change it, your application re-renders.

Another benefit is its decoupled nature. When using a single store, you have to register the structure, default values, etc. in a single place. You cannot modularize your code. With atoms, you can define them where ever you want. Lastly, atoms can be combined (in most implementations). This means you can use atoms in other atoms. When an underlying atom changes, the parent atom changes as well. You don't have to worry about re-render or listening, it is all managed for you.

It does have some downsides. When the number of atoms grows, managing them can become a hassle. You have to name them all, and you have to be aware that they exist. Also, managing a complex structure of dependencies between atoms can become quite a task for developers.

Reactivity and proxies

Many modern front-end frameworks are reactive. When a state changes, the framework knows that it should re-render. Or in other words, the state lets the framework knows it changed. This mental model is very like a proxy. A proxy is a wrapper object that is being called, instead of accessing the targeted object . This allows us to add custom behavior to various calls.

Proxies are ideal to create reactive and robust state management. The basic power lays in the fact that we can add listeners to state changes. Besides, the values of a proxy can directly be changed. You do not have to invoke the change via a function. If you want to create a more complex proxy, you could implement validators that validate changes before applying a state change. You could even add several layers of 'middleware' before each state change. You can go nuts.

const store = proxy(() => ({ count: 0 }));const listener = (c) => console.log('Count updated:', c);store.on('count', listener);store.count++;// Count updated: 1The code snippet above shows an example proxy. As you can see, we add a listener function for when the value of count changes. Now when we change the value of count, the listener function is triggered. Do note that this particular implementation is not immutable. You can change the value . Many people prefer to have an immutable state, as it is less prone to development errors.

Wrapping up

Now you should have a better understanding of some fundamentals of state management. Knowing the different types of state and how to manage state is the start. With proper state management, you can get a long way in complex web applications. But it is the start. There are many (more) ways to manage data that are important in client-side applications. When you master state, go dive into persistent storage or caching.

Original Link: https://dev.to/crinklesio/demystifying-state-management-2c1c

Dev To

An online community for sharing and discovering great ideas, having debates, and making friends

An online community for sharing and discovering great ideas, having debates, and making friendsMore About this Source Visit Dev To