An Interest In:

Web News this Week

- April 18, 2024

- April 17, 2024

- April 16, 2024

- April 15, 2024

- April 14, 2024

- April 13, 2024

- April 12, 2024

An Adequate Introduction to Functional Programming

This article is part of a series where we explore functional and reactive programming both in general terms and applied to JavaScript.

In this first post, we discuss several functional core concepts with a practical approach, dwelling on the theoretical part only if strictly needed. In the second one, well talk about functional streams, while in the third and fourth episodes well implement from scratch our version of RxJS.

Introduction

Functional programming models software as a set of pure functions, avoiding shared mutable state. For now, it is enough to know that a pure function is a function that doesnt modify the environment and its return value is the same for the same arguments. Meanwhile, the main issue with shared state is that it will decrease predictability and makes harder to follow the logic flow.

To be clear: different problems require different tools, it doesnt exist the perfect and universal paradigm, but there are a lot of situations where FP can bring advantages. Heres a summary:

- focus on what you want to achieve (declarative), not how (imperative)

- more readable code, which hides useless implementation details

- clear logic flow, state is less dispersed nor implicitly modified

- functions/modules became easily testable, reusable and maintainable

- safer code, without side effects

Why we care about imperative and declarative approaches? Lets discuss the difference with an example, which performs the same operation in both ways: filter out odd numbers from a list while incrementing to five the smaller ones.

const numbers = [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]// IMPERATIVE approachlet result = []for (let i = 0; i < numbers.length; i++) { if (numbers[i] % 2 === 0) { if (numbers[i] < 5) { result.push(5) continue } result.push(numbers[i]) }}// DECLARATIVE approachnumbers .filter(n => n % 2 === 0) .map(n => n < 5 ? 5 : n)Same computation, same result. But, as you can see, the imperative code is verbose and not immediately clear. On the other hand, the declarative approach is readable and explicit, because it focuses on what we want to obtain. Imagine extending the same difference to big parts of your applications and return to the same code after months. Your future self (and your colleagues also) will appreciate this declarative style!

Again, theres no best paradigm as someone may claim, only the right tool for a specific case, indeed Im also a big fan of OOP when implemented using composition (the Go "way). In any case, functional programming could find several places in your applications to improve readability and predictability.

Lets start to explore some FP core concepts. Well see how each of them will bring some of the advantages listed above.

Pure functions

A function is pure when:

- it has no observable side effects, such as I/O, external variables mutation, file system changes, DOM changes, HTTP calls and more,

- has referential transparency: the function can be replaced with the result of its execution without changing the result of the overall computation.

Lets clarify the definition with some basic examples.

// impure, modifies external statelet counter = 0const incrementCounter = (n) => { counter = counter + n return counter}// impure, I/Oconst addAndSend = (x1, x2) => { const sum = x1 + x2 return fetch(`SOME_API?sum=${sum}`)}// both pure, no side effectsconst add = (x1, x2) => { return x1 + x2}const formatUsers = users => { if (!(users instanceof Array)) { return [] } return users.map(user => ` Name: ${user.first} ${user.last}, Age: ${user.age} `)}Pure functions are safe because they never mutate implicitly any variable, from which other parts of your code could depend now or later.

It may seem uncomfortable to code with these restrictions but think about this: pure functions are deterministic, abstractable, predictable and composable.

Functions as values

In languages that support FP, functions are values, so you can pass and return them to and from other functions and store them in variables.

In JS we are already used to this pattern (maybe not consciously), for example when we provide a callback to a DOM event listener or when we use array methods like map, reduce or filter.

Lets look again at the previous example:

const formatUsers = users => { if (!(users instanceof Array)) { return [] } return users.map(user => ` Name: ${user.first} ${user.last}, Age: ${user.age} `)}Here the map argument is an inline anonymous function (or lambda). We can rewrite the snippet above to demonstrate more clearly the function as value idea, where the function userF is passed explicitly to map.

const userF = user => { return ` Name: ${user.first} ${user.last}, Age: ${user.age} `}const formatUsers = users => { if (!(users instanceof Array)) { return [] } return users.map(userF)}The fact that functions in JS are values allows the use of higher-order functions (HOF): functions that receive other functions as arguments and/or return new functions, often obtained from those received as inputs. HOFs are used for different purposes as specialization and composition of functions.

Let's look at the get HOF. This utility allows to obtain internal node values of objects/arrays safely and without errors (tip: the syntax ...props is defined REST, it is used to collect a list of arguments as an array saved in the parameter named props).

const get = (...props) => obj => { return props.reduce( (objNode, prop) => objNode && objNode[prop] ? objNode[prop] : null, obj )}Get receives a list of keys, used to find the desired value, and returns a (specialized) function which expect the object to dig into.

Heres a realistic example. We want to extract the description node from the first element in the array monuments from a not-always-complete object (maybe received from an untrusted API). We can generate a safe getter in order to do this.

const Milan = { country: 'Italy', coords: { lang: 45, lat: 9 }, monuments: [ { name: 'Duomo di Milano', rank: 23473, infos: { description: 'Beautiful gothic church build at the end of', type: 'Church' } }, { /* ... */ }, { /* ... */ }, { /* ... */ } ]}No need for multiple (boring) checks:

const getBestMonumentDescription = get('monuments', 0, 'infos', 'description')getBestMonumentDescription(Milan) // 'Beautiful gothic church'getBestMonumentDescription({}) // null (and no errors)getBestMonumentDescription(undefined) // null (same for null, NaN, etc..)getBestMonumentDescription() // nullFunction composition

Pure function can be composed together to create safe and more complex logic, due to absence of side effects. By safe I mean that we're not going to change the environment or external variables (to the function) which other parts of our code could rely on.

Of course, using pure functions to create a new one does not ensure the purity of the latter, unless we carefully avoid side effects in each of its parts. Let's take an example. we want to sum the money of all users that satisfy a given condition.

const users = [ {id: 1, name: "Mark", registered: true, money: 46}, {id: 2, name: "Bill", registered: false, money: 22}, {id: 3, name: "Steve", registered: true, money: 71}]// simple pure functionsconst isArray = v => v instanceof Arrayconst getUserMoney = get('money')const add = (x1, x2) => x1 + x2const isValidPayer = user => get('registered')(user) && get('money')(user) > 40// desired logicexport const sumMoneyOfRegUsers = users => { if ( !isArray(users) ) { return 0 } return users .filter( isValidPayer ) .map( getUserMoney ) .reduce( add, 0 )}sumMoneyOfRegUsers(users) // 117We filter the users array, we generate a second one with the money amounts (map) and finally we sum (reduce) all the values. We have composed the logic of our operation in a clear, declarative and readable way. At the same time, we avoided side effects, so the state/environment before and after the function call is the same.

// application stateconst money = sumMoneyFromRegisteredUsers(users)// same application stateBeside manual composition, there are utilities that help us to compose functions. Two of them are particularly useful: pipe and compose. The idea is simple: we are going to concatenate n functions, calling each of them with the output of the previous one.

// function composition with pipe // pipe(f,g,h)(val) === h(g(f(val)))const pipe = (...funcs) => { return (firstVal) => { return funcs.reduce((partial, func) => func(partial), firstVal) }}// or more conciselyconst pipe = (...fns) => x0 => fns.reduce((x, f) => f(x), x0)Pipe is a HOF that expects a list of functions. Then, the returned function needs the starting value, which will pass through all the previous provided functions, in an input-output chain. Compose is very similar but operates from right to left:

// compose(f,g,h)(val) === f(g(h(val))) const compose = (...fns) => x0 => fns.reduceRight((x, f) => f(x), x0)Lets clarify the idea with a simple example:

// simple functionsconst arrify = x => x instanceof Array ? x : [x]const getUserMoney = get('money')const getUserReg = get('registered')const filterValidPayers = users => users.filter( user => getUserReg(user) && getUserMoney(user) > 40)const getUsersMoney = users => users.map(getUserMoney)const sumUsersMoney = moneyArray => moneyArray.reduce((x, y) => x + y, 0)// desired logicexport const sumMoneyOfRegUsers = pipe( arrify, filterValidPayers, getUsersMoney, sumUsersMoney)// get resultsumMoneyOfRegUsers(users) // 117We could also examine each intermediate result using the tap utility.

// debug-onlyconst tap = thing => { console.log(thing) return thing}export const sumMoneyOfRegUsers = pipe( arrify, filterValidPayers, tap, getUsersMoney, tap, sumUsersMoney)// get resultsumMoneyOfRegUsers(users)// [{...}, {...}] first tap // [46, 71] second tap// 117 final resultImmutability & immutable approach

Immutability is a core concept in FP. Data structures should be considered immutable in order to avoid side effects and increase predictability. This concept brings other advantages: mutation tracking & performance (in certain situations).

To achieve immutability in JS, we must adopt an immutable approach by convention, that is copying objects and arrays instead of in place mutations. In other words, we always want to preserve the original data making new copies.

Objects and arrays are passed by reference in JS, that is, if referenced by other variables or passed as arguments, changes to the latter ones affects also the originals. Sometimes copying the object in a shallow way (one level deep) is not enough, because there could be internal objects that are in turn passed by reference.

If we want to break all ties with the original, we should clone, as we say, deep. Seems complicated? Maybe, but bear with me for a few minutes!

The most useful language tools to clone and update data structures are:

- the object and the array spread operator ( syntax ),

- arrays methods as map, filter and reduce. Both of them return a shallow copy.

Here some editing operations, performed with an immutable approach:

// OBJECT SPREAD OPERATOR const user = { id: 1, name: 'Mark', money: 73, registered: true}const updatedUser = { ...user, registered: false }// ARRAY SPREAD OPERATORconst cities = [ 'Rome', 'Milan', 'New York' ]const newCities = [ ...cities, 'London' ]In both examples, individual elements of the array and individual properties of the object are copied in a new array and in a new object respectively, which are independent from the original ones.

To edit, add or delete elements from an array of objects in an immutable way we could use a combination of spread operators and array methods. Each time we create a new collection with some variation, based on the specific task.

// originalconst subscribers = [ {id: 1, name: 'Tyler', registered: true, money: 36 }, {id: 2, name: 'Donald', registered: true, money: 26 }, {id: 3, name: 'William', registered: true, money: 61 }]// EDIT const newSubscribers1 = subscribers .map( sub => sub.name === 'Donald' ? {...user, money: 89} : user )// DELETEconst newSubscribers2 = newSubscribers1.filter( sub => sub.name !== 'Tyler' )// ADDconst newSubscribers3 = [ ...newSubscribers2, { id: 4, name: 'Bob', registered: false, money: 34 } ]Let's talk quickly about shallow and deep copies, starting with some code.

const subscribers = [ { id: 1, name: 'Tyler', registered: true, money: 36 }, { id: 2, name: 'Donald', registered: true, money: 26 }, { id: 3, name: 'William', registered: true, money: 61 }]// SHALLOW copyconst newSubscribers1 = [ ...subscribers ]// DEEP copy (specific case)const newSubsibers2 = subscribers.map( sub => ({...user}) )The difference between the two types of copies is that, if we change a property of an object in the shallow copied array the change is also reflected to the original, which does not happen in the deep copy. In the latter case this occurs because, in addition to the array cloning operation, we also clone the contained objects.

Both types of copy are usable and fine, as long as you always clone the parts that need to be modified. In this way we will never modify the original.

A general deep solution is made with recursive functions (which we should take from libraries for convenience and reliability). Deep copies are useful if we want to be completely free to manipulate data or if we don't trust third-party code.

A note on performance

Let's talk briefly about performance. There are certain situations where immutability can boost our apps. For example, a clone will be allocated in a memory location different from the original, allowing an easy and quick comparison by reference. Same pointer/reference (=== for objects)? No changes. Different reference? Change detected, so react properly. No need of internal comparisons, because we have decided to create separate copies for each change.

On the other hand, making new copies each time could generate a lot of memory consumption, leading to performance losses. This is a well-known intrinsic problem of functional programming, solved by sharing parts of the manipulated data structures between the clones. Anyway, this complex topic goes beyond the scope of the current article.

State management & side effects

At some point we need to use state, to save permanent variables, make some I/O, modify the file system and so on. Without these operations an application is just a black box. So, how and where to manage state and side effects?

Lets start from the basics. Why we try to avoid shared, mutable and scattered state? Well, the problem basically boils down to this idea: with shared state in order to understand the effects of a function, you have to know the entire history of every shared variable that the function uses or affects. Another way to put this problem is: functions/operations/routines that act on shared state are time and order dependent.

In conclusion, shared mutable state reduces predictability and makes harder to follow the logic flow.

Pure FP languages tend to push state and side effects at the borders of the application, to manage them in a single place. Indeed, the functional solution to this problem is to handle state in a single (large) object outside the application, updated with an immutable approach (so cloned and updated each time).

In the front-end development field, this pattern is adopted and implemented with so-called state-managers such as Redux, Vuex and NgRx. At a cost of more code (not so much) and complexity, our applications will become more predictable, manageable and maintainable.

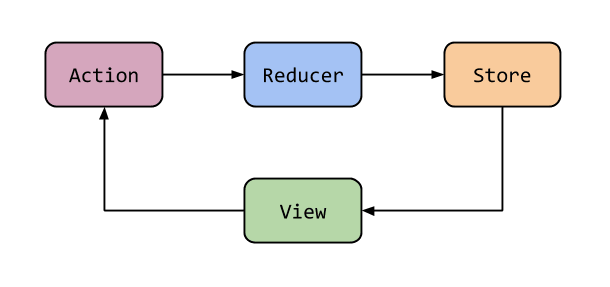

Here's how state-managers works, in a super simplified diagram. Events trigger actions that activate reducers, which update the state (store). As an end result, the (mostly) stateless UI will be updated properly. The argument is complex, but I briefly touched the topic to get you into the fundamental idea.

Furthermore, side effects are containerized and executed in one or a few specific points of the application (see NgRx effects), always with the aim of improving their management.

In addition, this pattern allows mutation tracking. What do we mean? If we update the application state only with immutable versions, we can collect them over time (even trivially in an array). As a result, we can easily track changes and switch from one application "condition" to another. This feature is known as time travel debugging in Redux-like state managers.

Conclusions

In the attempt to treat FP extensively, we didnt talk about some important concepts that we must mention now: currying & partial application, memoization and functional data types.

Talking in-depth about FP would take months, but I think that this introduction is already a good starting point for those who want to introduce the paradigm in some parts of their applications.

In the next article, well talk about functional streams, entering the world of reactive programming. Hope to see you there!

PS: English is not my mother tongue, so errors are just around the corner. Feel free to comment with corrections!

Original Link: https://dev.to/mr_b/an-adequate-introduction-to-functional-programming-1gcl

Dev To

An online community for sharing and discovering great ideas, having debates, and making friends

An online community for sharing and discovering great ideas, having debates, and making friendsMore About this Source Visit Dev To